Introduction

Before delving into the history of Crimea, it’s worth noting that the “Crimean Tatar” has developed a distinct identity based on geography as a result of migrant patterns from a specific region. The Crimean Tatars are said to have originated in this region. In this section, we will look at the history of Crimea, which is regarded the motherland, before looking at the existence of the Crimean Tatars in this geography and the process. The “Crimean Khanate” is said to be the beginning of the Crimean Tatars.

Short History of Crimea

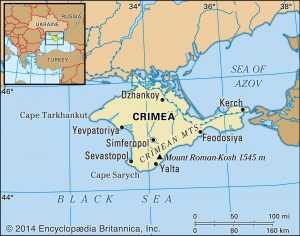

Crimea, a peninsula bounded on the west and south by the Black Sea and on the east and north by the Sea of Azov, is separated from the rest of the country by a 9-kilometer-wide and 20-kilometer-long dividing boundary. It covers over 26,000 square kilometers. Crimea was dubbed the Green Island because of its thin link to the mainland, which gave it the appearance of an island (Bala, 1967). In 1475, the Crimea enters the Ottoman rule, ushering in a new age. Crimea will thereafter become a hub of civilisation. Crimea became a Turkish-Islamic hub as new communities, inns, palaces, and mosques were built.

Agriculture and agriculture have progressed as well. The seventeenth century With Russia’s threat to Crimea, the Khanate’s links to the Ottoman Empire grew even stronger. After this day, the Russians took possession of Crimea, which had been under Ottoman administration until 1783. The Muslim Crimean Tatars, who were the dominant element of Crimea throughout the Soviet period, were evacuated from their nation following World War II, during the Tsarist period.

The demographic and historical appearance of the peninsula was attempted to be entirely transformed by introducing Russian and Ukrainian communities in their place. When the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991, the Tatars began to return to Crimea, which had become an independent republic under Ukraine (Gökçebay, 2006). Crimea is also strategically important from a geopolitical standpoint. Because of its geographical location, Crimea is on the quickest path from Russia to the Mediterranean. Crimea, particularly the straits, has retained its geographic importance throughout history as a result of the Black Sea’s domination.

Haji Giray Khan is listed as the founder of the Crimean Khanate in most historical records. In 1441, Hac Giray, son of the Cuci dynasty’s Gyâseddîn, announced the khanate’s existence by printing money in his name. In the 15th century, the Crimean Khanate was beset by internal strife, but the rise of the Genoese in the region prompted the Crimean Khanate to work with the Ottomans. Crimea was also near to other Turkish territories for the Ottomans, thus they consented to interfere. When Hacı Giray died in 1466, his sons fought for the throne and caused confusion. In 1475, Fatih Sultan Mehmet sent Gedik Ahmet Pasha with a strong navy and conquered Kefe and all the Genoese ports on the Crimean coast (Aslanapa, 1983).

The Crimean Khanate was split from the Ottoman Empire and established an autonomous khanate with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774), which was signed as a result of the Ottoman-Russian conflict of 1773-1774. However, the autonomous Khanate remains militarily weak, and Crimea is officially given to Russia via the “Yaş Treaty” signed in 1792. Following that, Russian tsarina Catherine II conquered Crimea and began settling Greek and Slavic populations there in order to exploit the Crimea’s strategic importance and disturb the Tatars’ demographic predominance in the region (Ersoy, 2008).

Exile of 1944 and Evacuation of Crimea from Tatar

Many diverse countries or communities in various geographies have endured forced migrations and exiles throughout history. However, it is clear that Muslim-Turkish components were in the vanguard of the groups that were most exposed to mass exile movements in the ages, mostly owing to political causes, notably in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Sarısır, 2006). Crimean Turks are also prominent among this group. The wholesale expulsions of countless people in the 1940s were one of the worst chapters in Soviet Russia’s history (Kalkan, 2007).

The goal of integrating all the countries residing on Soviet Russia’s territory around an equal and equitable system was at the heart of Soviet Russia’s forced migration and exile program (Tuğul, 2003). Crimean Turks were among those accused of treason to the Soviet Union and denied the right to defend themselves, with the majority of them being compelled to migrate to the Soviet Union’s Asian regions.

When physical and cultural annihilation against Crimean Turks failed to produce the intended results, preparations were devised to remove the Crimean Turks entirely. The major calamities for the Crimean Turks (Koçak, 2014) began after Stalin issued a directive on May 11, 1944, ordering the evacuation of the Crimean Turks from Crimea to the last individual (Kırımlı, 2002). This event, which is one of the biggest genocides in the history of exile and international crimes against the Crimean Turks, started after the decision signed by Stalin on May 11, 1944, which included the deportation of all Crimean Tatar Turks.

The Annexation Process of Crimea Today

To begin, it should be mentioned that the EU and NATO’s aim to incorporate former Soviet republics that proclaimed independence drew Russia’s attention and agitated it throughout the post-Soviet period. Russia has begun to apply sanctions on the nations that have broken away from itself. Ukraine has been stuck between Russian sanctions and diverse Western policies, and distinct perspectives have emerged from both the government and the opposition. Despite the fact that Yanukovych’s administration has pursued a pro-Russian strategy, opponents want Ukraine to join the EU with the help of the West (Konak, 2019).

Did the Russians feel obligated to these nations because the peoples of the region were ethnically Russian during the Soviet era, or did they have other motives? However, it should be noted that while the Soviet Union was disintegrating, it always left a problem in other regions; The Crimean problem, which it has problems with Azerbaijan-Armenia, Uzbekistan-Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine, can be given as an example. The Ukraine crisis began in November 2013, when the Ukrainian government shifted its foreign policy and moved closer to the West, resulting in the annexation of Crimea. Russia has exploited energy as an instrument in its foreign policy in the past.

However, in Ukraine, it went a step further and utilized the ethnic Russian population to achieve its foreign policy objectives (Ağır). When we look at the Ukraine, they want to develop their foreign policy relationships with EU but Russia given minus for this attemption. With this attemption, EU came to the border of the Russia so Russia apply some embargo for Ukraine. Whereas, the opposition protested President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision not to sign a partnership agreement with the European Union in favor of cooperating with Russia in Independence Square in Kiev, and the opposition demonstrations were attempted to be suppressed by the police, raising tensions even higher (İmanbeyli, 2014).

After Viktor Yanukovych fled to Russia, the Ukrainian Parliament deposed the president, formed a transitional administration, and informed the public of the shift of power. While attempting to mitigate the impact of Kiev’s political impasse, which pits Russia against the West, Russia, which saw the crisis and administrative vacuum as an opportunity, predicted that Ukraine’s ties with the European Union will improve on February 27, 2014. Then, fearing that it would become a member of NATO and that the situation would pose a threat to itself, Russia invaded the territory by landing special troops in the Crimean peninsula, which is strategically important for unification and where the Russian population is concentrated. Following Ukraine’s approach to the European Union, Russia developed a rift with the former Soviet republic.

Ukraine’s population are divided into two poles, pro-Russian and pro-Western, since the country is physically divided between Europe and Russia. Later, the unrest extended to Crimea and Donbas. The Crimean Parliament has resolved to call a referendum on Crimea’s annexation via Russia.

Despite the protests of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians, Russia unlawfully seized Crimea following a contentious referendum on March 16, 2014 (Council on Foreign Relations, June 10, 2021). Pro-Russian rebels also claim sovereignty of eastern Ukraine, including the Donbas area, which they have occupied for the previous seven years unlawfully. In February 2014, pro-Russian separatists attacked pro-government forces in the Donetsk and Luhansk (Donbas) areas.

The two regions are extensively populated by individuals of Russian ancestry. Separatists acquired large weaponry and ammunition from Russia, according to the Kyiv administration. Separatists declared two so-called republics, Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic, on May 11, 2014, in a phony referendum. From the Russian-Ukrainian border, where the Kyiv administration lost control, Russian military vehicles and heavy armaments invaded Donbas. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) reported on this issue, which Russia rejected (The Economic Times , April 16, 2021).

Figure 1: Mapping the Russian Forces

Source: Deutsche Welle (DW ).

The Importance of Ukraine Demographic and Strategic

In terms of politics, Ukraine is a unitary nation state, yet it is home to a number of ethnic minorities. When looking at the list of ethnic minorities in Ukraine, it is clear that two distinct classification systems have been used. Ukraine is the European continent’s biggest country. The geopolitical position of Ukraine is far more crucial. In H. Mackinder’s “Heartland Theory,” Ukraine is located in the Eurasia area, which is referred to as Kalpgah (Heartland) (Sarıkaya, 2017). Russia’s aggressiveness in Ukraine has produced Europe’s worst security crisis since the Cold War, owing to a variety of circumstances. During the Cold War, Ukraine was a centerpiece of the Soviet Union, the US’s archrival. It was the most populous and powerful of the fifteen Soviet republics, second only to Russia in terms of population and power. It was home to much of the union’s agricultural production, defense industry, and military, including the Black Sea Fleet and portion of the nuclear arsenal. Ukraine was so important to the union that its decision to break relations in 1991 was a death blow to the beleaguered superpower.

In 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and began arming and abetting separatists in the Donbas area of Ukraine, the country became a battleground. The annexation of Crimea by Russia was the first time a European country had done so since World War II. The violence has claimed the lives of almost 14,000 people, making it Europe’s worst since the 1990s Balkan Wars. Russia and Ukraine share strong cultural, economic, and political ties, and Ukraine is an important part of Russia’s identity and global vision.

Why Russia focused on Ukraine and Crimea?

- Relationships with family- Russia and Ukraine have a long history of deep familial ties. Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital, is frequently referred to as “the mother of Russian cities,” equaling Moscow and St. Petersburg in terms of cultural importance. Christianity was transmitted to the Slavic peoples from Byzantium in Kyiv in the eighth and ninth century. And it was Christianity that held Kievan Rus together, the early Slavic kingdom from which current Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians descend (Masters, February 5, 2020 ).

- The Russian diaspora- is a term used to describe a group of people who The wellbeing of the nearly eight million ethnic Russians residing in Ukraine, especially in the south and east, is one of Russia’s top priorities, according to a 2001 census. As a justification for its operations in Ukraine, Moscow claimed a responsibility to defend these individuals (Masters, February 5, 2020 ).

- Qualification of superpower- following the fall of the Soviet Union, many Russian leaders saw the breakup with Ukraine as a historical blunder and a danger to Russia’s status as a great power. Many saw Russia’s international standing being harmed by losing a lasting grip on Ukraine and allowing it to drift into Western hands(Masters, February 5, 2020 ).

- Crimea is a region in Ukraine- Crimea was ceded from Russia to Ukraine by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in 1954 in order to establish “brotherly links between the Ukrainian and Russian peoples. Since the union’s dissolution, many Russian nationalists in both Russia and Crimea have yearned for the peninsula’s restoration. The Black Sea Fleet, Russia’s major marine force in the region, is based at Sevastopol(Masters, February 5, 2020 ).

- Trade is an important aspect of life- Although Russia is Ukraine’s major commercial partner, the relationship has deteriorated in recent years. Russia had wanted to include Ukraine into its single market, the Eurasian Economic Union, which now includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, prior to its invasion of Crimea(Masters, February 5, 2020 ).

- It’s all about the energy- Russia provided the majority of Ukraine’s gas until the annexation of Crimea, following which supplies slowed and eventually ended in 2016. Russia, on the other hand, continues to rely on Ukrainian pipelines to transport its gas to clients in Central and Eastern Europe, and pays Kyiv billions of dollars in transit costs each year. Russia was nearing completion of Nord Stream 2, a gas pipeline over the Baltic Sea that some have warned might deprive Ukraine of vital money in early 2020. Russia, on the other hand, has a commitment to continue transporting gas via Ukraine for several more years(Masters, February 5, 2020 ).

- Influence in politics- After its favoured candidate for Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych, lost to a reformist challenger as part of the Orange Revolution popular movement in 2004, Russia has been determined to maintain its political influence in Ukraine and across the former Soviet Union.

The shock in Ukraine came after a similar election setback for the Kremlin in Georgia in 2003, dubbed the Rose Revolution, and another in Kyrgyzstan in 2005, dubbed the Tulip Revolution. In 2010, Yanukovych was elected President of Ukraine, despite voter dissatisfaction with the Orange administration(Masters, February 5, 2020 ).

Crimean Issue and EU

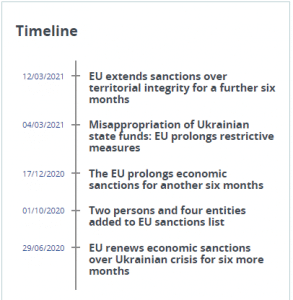

Without Ukraine’s authorization, the European Union opposes the building of the Kerch Bridge and the commissioning of a railway portion. This is a new effort to forcefully incorporate the unlawfully seized peninsula into Russia, as well as a new violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. Illegal limitations on such transit continue, posing a financial burden on Ukraine’s ports in the Azov Sea, as well as the area as a whole.

Figure 2: Diplomatic ways

Source: European Council (EU restrictive measures in response to the crisis in Ukraine).

The human rights situation in the Crimean peninsula has worsened substantially since the Russian Federation’s unlawful annexation. In light of the European Court of Human Rights’ landmark decision of 14 January 2021, the European Union demands that Russia fully comply with international humanitarian law, international human rights standards, and relevant UN General Assembly Resolutions, including Resolution 75/192 of 16 December 2020. Residents of the peninsula have their fundamental liberties, such as freedom of expression, religion or belief, and association, as well as the right to peaceful assembly, severely curtailed.

Journalists, human rights advocates, and defense attorneys are all subjected to harassment and intimidation in the course of their job. Crimean Tatars are still being harassed, pressed, and their rights are being severely infringed. Crimean Tatars, Ukrainians, and all other ethnic and religious groups on the peninsula must be given the opportunity to preserve and develop their culture, education, identity, and cultural heritage traditions, which are presently endangered by the illegitimate annexation. Destructive efforts against the peninsula’s cultural wealth, including archaeological riches, artworks, museums, and historical places, must come to an end (Council of European Union, 25 February 2021).

NATO and Russia

As NATO expanded eastward into post-Soviet republics, Russia’s authority and sphere of influence dwindled even further. Two key issues are highlighted in Russia’s 2015 National Security Strategy: Russia has proved its capacity to maintain its own sovereignty, independence, state and territorial integrity, as well as the rights of its citizens living abroad. The Russian Federation’s involvement in addressing the world’s most pressing issues, ending armed confrontations, and guaranteeing strategic stability and international law’s dominance in interstate relations has grown.

Besides, The North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) military potential and endowment with global functions in violation of international law, the galvanization of bloc countries’ military activity, the alliance’s further expansion, and the location of its military infrastructure closer to Russian borders are all posing a threat to national security. Russia’s complaints with the West must be reconsidered. NATO is not an imminent, urgent threat militarily since neither NATO nor Russia are interested in a full-scale conflict, but Putin properly sees western-backed democracy as a challenge to his rule.

Russia should make attempts to engage in practical peace proposals with Ukrainian authorities as part of its grand strategy in Ukraine. It’s vital that Russia recognizes the necessity of retaining control of Crimea, but losing control of most of Eastern Ukraine should be a reasonable compromise (Schmidt, July 6, 2020).

Shortly;

Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military activities in eastern Ukraine have upended post-Cold War norms that had brought stability and progress to former Soviet—now sovereign—countries bordering Russia. Neighboring nations are rethinking their security and foreign policies in light of Ukraine, evaluating their own security and conflict dynamics in light of Russia’s new aggressive policies and practices in Ukraine, as well as the West’s reaction.

The US Institute of Peace (USIP) undertook a scenario study to better understand these newly developing trends and dynamics, looking at a medium-term, regional perspective to uncover the forces and variables driving the possibility for more conflict. This research produced a series of appealing narratives that serve as a framework for comprehending the region’s growing conflict dynamics. The war in Ukraine has become a flashpoint, with responses spreading beyond Russia’s neighboring republics. Countries in the area are putting new Russian-Western interaction, regional alliances and ties, and regional conflict dynamics to the test.

These stress tests are perilous in the context of the region’s frozen conflicts, and they might spark further bloodshed (Lauren Van Metre, March, 2015). Over several decades, Europe has made significant investments in the development of a system of norms, processes, and organizations for conflict prevention and crisis management. The quick descent from political instability to military conflict in Ukraine in 2014 shown that the procedures are still insufficient to meet the situation. The illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia without the agreement of Ukrainian authorities posed a serious threat to the European security order (STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE).

Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Aleksey Reznikov stated that the support given to European and Euro-Atlantic integration in his country has decreased by 5 percent in the last 2 years (Sputnik). Even though the commencement of Russia’s army pullout lowers tensions, the problem that precipitated the conflict remains unsolved. Some speculated that Russia was planning to invade eastern Ukraine or seeking for a chance to deploy peacekeepers before making its decision, while others speculated that the Kremlin was testing Biden’s patience. Current developments continue to happen.

Sümeyra Tahta

Stratejik Ortak Misafir Yazarı

[irp posts=”28645″ name=”Atlantik-Avrasya-Avrupa Üçgenin Kırım İlhakı”]

References

(tarih yok). US aims to mediate Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Ağır, O. (tarih yok). Rusya- Ukrayna Krizi’nin Avrasya Ekonomik Birliği Bağlamında Değerlendirilmesi. http://acikerisim.ksu.edu.tr:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/ksu/324/16%20RF-UKR.%20K.%20AEB.%20BA%C4%9E.%20DE%C4%9E..pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Aslanapa, O. (1983). Kırım Tarihi . İstanbul : Emel Kırım Vakfı.

Bala, M. (1967). Kırım. İstanbul.

Council of European Union. (25 February 2021). Ukraine: Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union on the illegal annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2021/02/25/ukraine-declaration-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-european-union-on-the-illegal-annexation-of-crimea-and-sevastopol/.

Council on Foreign Relations. (June 10, 2021). Conflict in Ukraine. https://microsites-live-backend.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine.

DW . (tarih yok). https://www.dw.com/en/us-aims-to-mediate-russia-ukraine-conflict/a-57427521. Deutsche Welle, https://www.dw.com/en/us-aims-to-mediate-russia-ukraine-conflict/a-57427521.

Ersoy, İ. (2008). DİASPORA ve KİMLİK: ESKİŞEHİR ve İSTANBUL’DA YAŞAYAN KIRIM TATARLARI’NDA ÇOKLUKÜLTÜREL KİMLİĞİN İFADE ALANI OLARAK “TEPREŞ”. İzmir: Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi, Güzel Sanatlar Enstitüsü, Doktora Tezi.

EU restrictive measures in response to the crisis in Ukraine. (tarih yok). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/ukraine-crisis/, see more: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/ukraine-crisis/history-ukraine-crisis/.

Gökçebay, Ö. (2006). TÜRKİYE’YE YERLEŞEN TATARLARDA DİNİ HAYAT VE ADETLER. Konya: Selçuk Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Yüksek Lisans Tezi.

İmanbeyli, V. (2014). Ülke-İçi Krizden Uluslararası Soruna Ukrayna-Kırım Meselesi. Seta Perspektif.

Kalkan, M. (2007). Sovyetler Birliği’nin ve Rusya Federasyonu’nun Orta Asya Üzerindeki Stratejik Planları. İstanbul: Bilge Kültür Sanat Yayınları.

Kırımlı, H. (2002). Kırım. 458-465.

Koçak, M. (2014). Rusya’nın İlhakı Sonrası Kırım ve Kırım Tatarları. Seta Perspektif , 1-8-45.

Konak, A. (2019). The Ukraine Crisis Resulting in the Annexation of Crimea and Its Economic Effects. International Journal of Afro-Eurasian Research (IJAR), https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/786830.

Lauren Van Metre, V. G. (March, 2015). The Ukraine-Russia Conflict Signals and Scenarios for the Broader Region. UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE, https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/SR366-The-Ukraine-Russia-Conflict.pdf.

Masters, J. (February 5, 2020 ). Ukraine: Conflict at the Crossroads of Europe and Russia. Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/ukraine-conflict-crossroads-europe-and-russia.

Sarıkaya, B. (2017). Evaluation of The Ukrainian Crisis Within The Context of Regional Security Complex Theory. Afro Eurasian Studies Journal , 33-53, https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/700186.

Sarısır, S. (2006). Demografik Oyun Sürgün. İstanbul: IQ Kültür Sanat Yayınları.

Schmidt, C. K. (July 6, 2020). Evaluating Russia’s Grand Strategy in Ukraine. E- IR Info, https://www.e-ir.info/2020/07/06/evaluating-russias-grand-strategy-in-ukraine/.

Sputnik. (tarih yok). Ukrayna Başbakan Yardımcısı Reznikov: Ülkemizde AB destekçilerinin sayısında düşüş var. https://tr.sputniknews.com/avrupa/202106061044669555-ukrayna-basbakan-yardimcisi-reznikov-ulkemizde-ab-destekcilerinin-sayisinda-dusus-var/.

STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE. (tarih yok). The Ukraine conflict and its implications. https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2015/03.

The Economic Times . (April 16, 2021). Explained: What’s behind the conflict in eastern Ukraine? https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/explained-whats-behind-the-conflict-in-eastern-ukraine/articleshow/82101803.cms?from=mdr.

Tuğul, S. (2003). SSCB’de Sürgün Edilen Halklar. İstanbul: Chiviyazıları Yayınları.

US aims to mediate Russia-Ukraine conflict. (tarih yok). https://www.dw.com/en/us-aims-to-mediate-russia-ukraine-conflict/a-57427521.

[/vc_toggle]